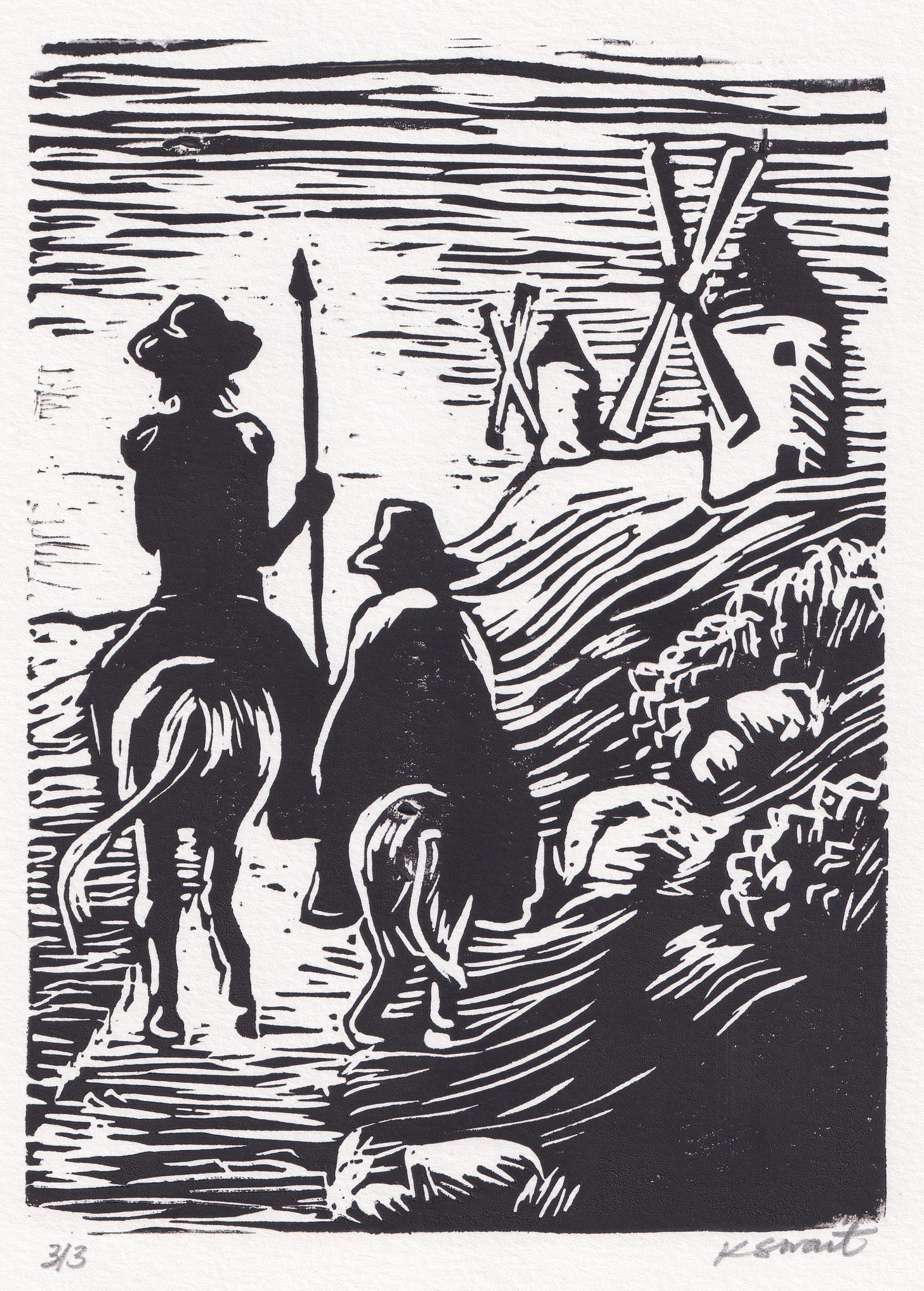

This essay is part of The Knight of Sad Semblance, my translation project. You may pre-order and support the translation at the button below. Supporters of the project, including paid Substack subscribers, can follow along with the translation as it progresses.

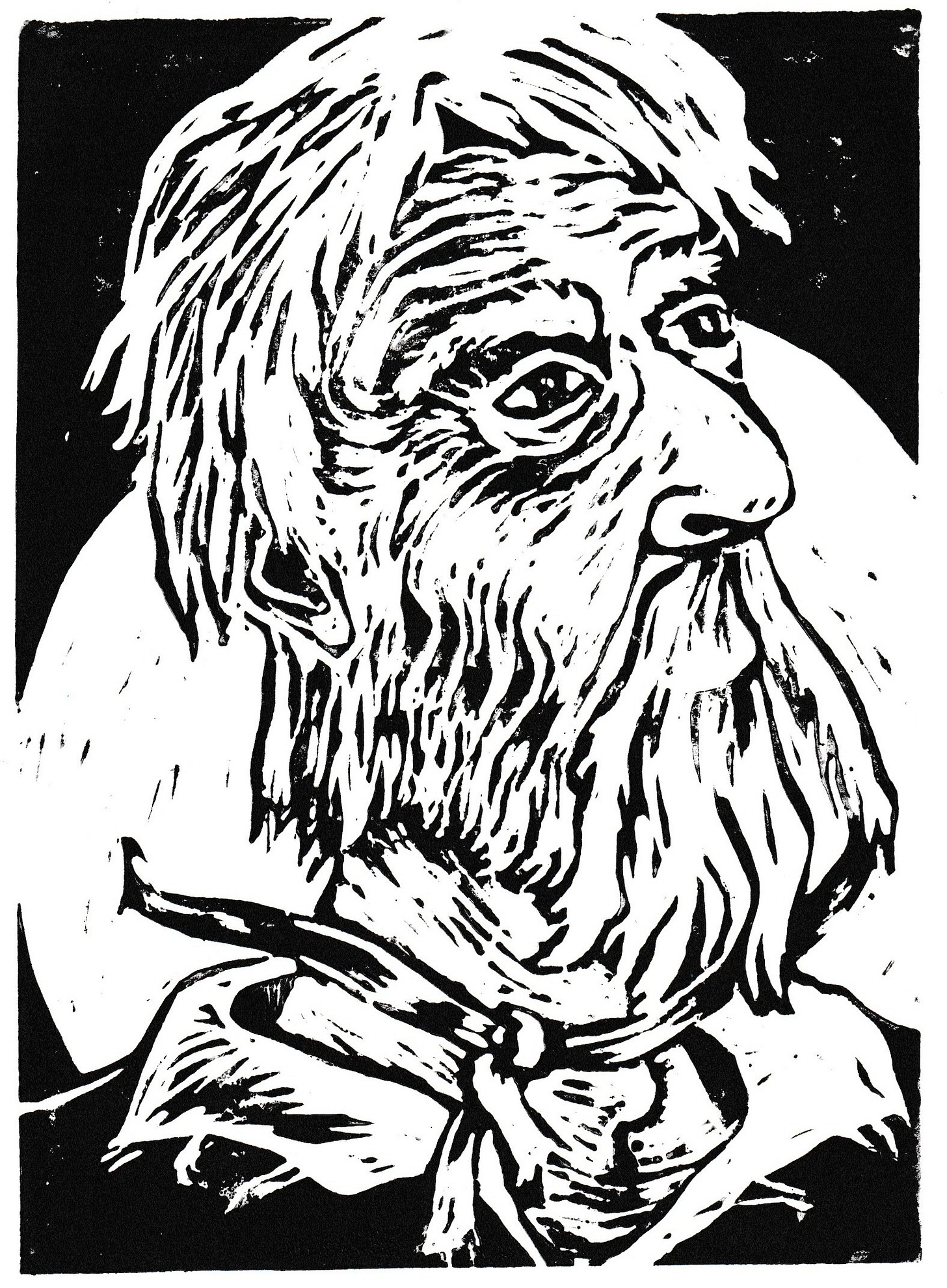

"I was Don Quixote of La Mancha, and now I am, as I have said, Alonso Quixano the Good."

The modern novel is an expression of demos divine

I would like to begin with an extended quote of Colombian philosopher (to some, “political theologian”) Nicolás Gómez Dávila, from a collection entitled simply Textos.1

A miasma of inanity emanates from good novels as if from a cemetery of atheists.

This literary genre, whose ambition is to trace the parabolic curve of life from its feces-smeared beginnings to the rattling breaths which are prelude to the final indifference, is ignorant of life’s capricious starts and sudden interruptions. Meanwhile and on the contrary, other arts know how to section the abrupt chunks of existence and launch them, peerless, isolated, dangling, into the aesthetic space that absolves them of their vulgar nexuses.

Tragedy, lyrical poetry, and the tale itself submit the representation of life to their own whimsical purposes. They disdain faithful reproduction, and nothing ties them to the monotony of our common condition. Upon the scaffolding that they quickly throw up an astute system of gestures elaborates a noble effigy of Man.

But the novel, with its longing to be a faithful and luminous shadow, weighs us down and knocks us to our knees when its terse mirror reflects our true destiny.

As we are rooted in the enduring thickness of the moment, the commiserable necessity of living allows us to avoid a holistic vision of life. We forget that our passing illuminations are drowned in the continuity of days, that the matte and spongy material of life absorbs our momentary exaltations. Encloistered within its successive urgencies, our puerile and sinister existence hides its indomitable fastidiousness.

But the novel delivers a complete life into our awareness of the instant. In its sudden and fleeting fulgor a finished existence teaches us, at last, pallid and obvious truths. The last and most trivial truth, that life creeps and slithers through the years until it recoils, is condensed into a single thorn of light.

In this we see the vain impatience of our youth lose itself in the marshes of senile years, and this terrain of reeds and mud extends its low horizons out to the shore of a hypothetical sea.

In this we learn that only the catastrophe that man accepts, only the death that takes in and shelters, only the disaster that takes up its own guilt, exempts him from the horrific patience of a forgotten convict in an indefinite exile.2

You say Don Quixote is the first modern novel. That may be, and I will allow you to make your case, but may I ask three questions first?

What does “first” mean?

What does “modern” mean?

What does “novel” mean?

The novel can as beautiful as a wetland and ugly as a swamp, a “terrain of reeds and mud” in the “marshes of senile years”.

Even when a novel strives for and achieves real beauty, not confusing its own subjective veracity or verisimilitude with “authenticity”, as if that had some value of its own, it does so by looking down and in. The novel longs for the low. Where most artforms strive to exalt man and unmoor him from the mud, novels are prized for realism, which is to say, mundane quotidian horror. So embedded is this way of thinking that many will read this and make against me atheistic accusations of fantasy (as if that were a crime) and cowardice, as if I had not the courage to look upon either universe or abyss as they do.

There are two ways to get into the heavens. One is to climb up into them; the other is to drag them down to us.

The tendency of the novel is to normalize, and therefore, to flatten.

The great democratic project

The novel is part of the great democratic project, which is the project of making man into god, above us only sky. Nicolás Gómez Dávila calls democracy an “anthropotheist religion whose principle is to choose a religious character, by which man takes up man as God. Its doctrine is a theology of man-god, its practice is the actualization of its principle in behaviors, in institutions, in works. The divinity which democracy attributes to man is no rhetorical flourish, no poetic image, no innocent hyperbole, but is, at last, a strict theological definition. Democracy proclaims us…”3

For Gómez Dávila, the historical arc and enterprise of democracy builds in three stages.

First, its birth. “Democracy registers its baptism upon the sneering face of Boniface VIII.”4 Boniface was a pope of the turn of the 13th century into the 14th. He did great violence with swords spiritual and secular, seizing as much power for the papacy as he could. While Boniface yet lived, Dante exiled him in imagination to the eighth circle of Hell, with the simoniacs. Unam Sanctam (1302) declared that salvation required submission to the Roman pontiff, and this included kings; it explicitly formulated a doctrine in which the church held the spiritual sword and the secular sword: duo gladii sunt in potestate Ecclesiae, spiritualis videlicet et temporalis. Most histories anachronistically see Boniface’s maneuverings as continuing the earthly traditions of the popes, as an effort to keep up with the growing power of Philip IV in France or the Habsburgs of the Holy Roman Empire. In fact, this was a significant change: it was an attempt to turn the papacy into a secular kingship. Kings, magistrates, jurists, and theologians reacted swiftly and violently against Boniface’s reach. In this reaction, “Caesarean legislators resurrect in order to restore tribunal powers.5 The modern state has been born.”6 The emergence of the sovereign state then takes place over several centuries. The medieval state is held in check by fealties and the obscurities of lawyers, but these are shed with the passing of time. We begin to see “the state that esteems itself sole judge of its own actions and the final court of appeal to its own plaints, that complies only with that which its own will adopts, whose own interests are the supreme law, and therefore makes itself a secularized god.”7 This is the state of the Sun King, the state of absolutist monarchism.8

"The second stage of the democratic invasion begins when man claims, within the framework of the sovereign state, the sovereignty that this doctrine grants him." The time of the Sun King is past. Now we have the French Revolution. Now we have Rousseau. According to Gómez Dávila, “every democratic revolution consolidates the state.”9 At this stage of democracy, the state is already god, it is omnipotent. The people do not rebel against the almighty state, this cannot even occur to them. They rebel against its current custodians. The people clamor for the liberty of being their own tyrants. At this point in history, Rousseau proclaims popular sovereignty, but constructs a “juridical tool” to control it: bourgeois covetousness. Economic function predominates. There is no gratitude, because there is nowhere to point it. Economic power in bourgeois society does not merely accompany or give luster to social power, but rather, creates it. “The veneration of riches is a democratic phenomenon. Money is the only universal value that the pure democrat abides by, because it symbolizes a chunk of usable nature, and because its acquisition may be credited solely to human effort. The cult of work, through which man adulates himself, is the engine of capitalist economy… The thesis of popular sovereignty delivers the steering of the state to economic power… Whoever tolerates a religious compunction that might disquiet the prosperity of a business, or an ethical argument that might suppress a technical advancement, or an aesthetic motive that might change some political project, wounds the bourgeois sensibility, and betrays the democratic enterprise.” This popular sovereignty and rapacious economic pursuit must culminate in a “petty individualism, where ethical indifference prolongs itself into intellectual anarchy…in each liberated man a sleeping simian yawns and arises.”10

“The third stage of the democratic conquest is the establishment of a communist society. The classic framing of the Manifest requires no rectification whatsoever: the bourgeoisie procreates the proletariat which eliminates it. Communist society emerges from the process which engenders a militant proletariat, a social grouping pulverized into solitary individuals, and an economy whose increasing integration requires a coordinated and despotic authority; but the process itself, and its political triumph, results from the religious purpose which sustains it. Communism is not a dialectical conclusion, but a deliberate project. In the communist society democratic doctrine may unmask its ambition. Its goal is not the simple happiness of humanity today, but the creation of a man whose sovereign power may take up the management of the universe. Communist man is a god who walks the dust of the earth.”11

According to this then, the arc of democracy, whose agenda is anthropotheistic, is 1. abolish the heavens, 2. make popular men sovereign, 3. make one man, our avatar, into God.

Last December I posted an article entitled Is It Time for the Novel to Die? on my main Substack, which I wrote to comfort the dying (if the novel is indeed dying for the umpteenth time) and to exalt other art forms. For the second time, I will ask you to read a lengthy quote, and this time, I have the temerity to quote myself.

At university I was taught a certain truth, but through the lens of the Enlightenment: novels were thought decadent by many in the 18th and early 19th century. The story of the emergence of the novel is often told in conjunction with the myth of progress, that is, modern novels are a natural and necessary growth and early novel-despisers were unenlightened troglodytes. The manner in which novels were consumed began to change as Rousseauism Voltairism Romanticism dovetailed with increasingly cheaper book production. Novels became more niche, and many were written for private and intimate consumption. Gothic romances emerged. People, especially women, started reading privately, and *gasp* even in bed. If we examine the perception that novels were decadent with some sympathy rather than chronological snobbery, we might grant that it doesn’t take much for novels to become masturbatory. I do not mean by this that novels are a literary spank bank; rather, readers often use them for affirmation, confirmation, soothing, and private vindication. This is harder to do with literature written for the open air, or for family reading.

I love novels. I was raised by Lord of the Rings. And of course, as soon as I say that, serious literary people dismiss me. Why?

It is interesting that many of the novels favored by Christians (Tolkien, Lewis, O’Connor, Charles Williams, MacDonald) have something of the medieval romance in them.

Lewis may actually be a divider of waters. Think of the "space trilogy”. The whole thing is very medieval. Suggestion: if Perelandra is your favorite, you are a lover of romance; if you prefer That Hideous Strength, you are a lover of the modern novel.

I love novels, but I hate Cormac McCarthy. Well, I read a bit of him once and hated it; nihilism oozed off the page… The synecdochic conflation of the novel with literature has destroyed the critical and artistic mind of the literary set.

Good art struggles for exaltation and glory, works to “elaborate a noble effigy of Man”. Again, the tendency of the novel is to pulverize/normalize, and therefore, to flatten.

What did I mean when I said that the novel is part of the great democratic project? I mean that it follows the same arc, and has the same agenda: supremacy through debasement, radical freedom through the destruction of all values, the deconstruction of life by the dread of living, the abolition of man by the denomination of the everyday as absurd.

This is not to say that every novel or every novelist has this agenda, but rather that modern art and artists have modern agendas. And so we return to that phrase, so often used with Quixote. The modern novel.

Maybe we need to redefine the novel

Earlier I asked what was meant by each word in the phrase “first modern novel”, which is ascribed to Quixote more than any other work, and that by far.

The problem is not with “novel”, but with “first” and “modern”.

The problem is that the novel has been coopted by writers who wish to make little of God, man, and the world, who wish to be one-eyed kings in a world of blind men.

I asked AI why the Quixote is considered the first modern novel. Here are two of its answers:

Its prose breaks from medieval romance with self-aware narration, psychological realism, and social satire—defining traits of the modern novel. It’s the pivot from episodic tales to character-driven complexity.

and

Don Quixote (1605) reigns as "first modern novel" for inventing realism and irony.

The second, of course, is a howler, one which would probably embarrass the model-builders. I’ll hold onto it, though, as emblematic of what people actually think and are taught…but usually don’t say quite so boldly.

The Tale of Sinuhe, an Egyptian prose fiction, dates to around 2000 years before Christ. Geraldine Pinch called it “the first historical novel”.

The Satyricon is a picaresque story of debauchery and sex, and Philip Corbett said it was “the first realistic novel”. Makes you wonder what Philip got up to in the evenings.

The 1st century Greek prose romance Callirhoe has jealous murders, pirate kidnappings, and a romantic reunion at the finale. B. P. Reardon and Ewen Bowie called it “the first European novel”.

The Tale of Genji, from around the year 1000, is a family epic set in realistic society, with internal monologues and everything. The presence of psychological depth and character development (gasp! wonder!) led Edward Seidensticker to call it “the first true novel”.

Ephesian Tale, The Golden Ass, Leucippe and Clitophon, Aethiopica, Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri, Prose Edda, The Alexander Romance, The Vulgate Cycle, The Decameron.

Need I go on? Any objection to calling these prose works “novels”, as we understand the word, may be answered by pointing to modern examples in which the same so-called bugs are features.

No one who has read the ancients with even a modicum of respect would think that irony, realism, social satire, or self-aware or unreliable narrators were a modern invention. The thing is, people who have read the ancients with respect are vanishingly rare, and so the arrogance and ignorance of our age builds its narrative: progress progress progress dust dust dust.

We will save the novel by throwing out the modern novel.

Quixote is not Candide

This is the best of all possible worlds.

There are two men credited with inventing calculus. One is Sir Isaac Newton, and the other is Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz was a man in full, a “many-sided genius”12 whose epistemological work is studied to this day. In 1710 he wrote Essays of Theodicy upon the goodness of God, the liberty of man and the origins of evil. In it he claimed, at greater length and depth, of course, that because God is the greatest good13 this must be the best of all possible worlds.

Anyone who has an appreciation for Anselm of Canterbury would recognize this; Leibniz’s novelty, if any, lay in his formulations of particular laws of logic to build his arguments toward his optimistic end:

This is the best of all possible worlds.

A disgusting idea to anyone craving the freedom to rule himself as a sovereign individual yet frustrated at his impotence to make the world as he wished it to be. A concept revolting to anyone obsessed with dust and mud.

Such a man was Voltaire. The conclusions to be drawn from an angelically practical optimism were unbearable. Leibniz must be attacked, must be ridiculed. Voltaire had to show that life is nothing but pain and shit and blood and meaningless sex and lots and lots of overwhelming death.

So of course, he decided to write a novel.

In 1759, Candide was born.

Candide is nasty and low.

Candide is extremely democratic.

This literary genre, whose ambition is to trace the parabolic curve of life from its feces-smeared beginnings to the rattling breaths which are prelude to the final indifference, is ignorant of life’s capricious starts and sudden interruptions.

Wait…what could be more capricious than Candide?

Ah, here you are mistaken. We associate disaster with caprice, yet we have no gods. Caprice requires agency, some goat god; it is not a synonym for random. Candide is relentless, inexorable, in its agenda. Any whiff of goodness is crushed or ridiculed. The optimistic Pangloss, a stand-in for Leibniz, is given to venial sin and catches syphilis, which destroys his body. There is no one righteous, no, not one.

Candide is expelled from a baron’s castle after being caught kissing Cunégonde, the baron’s daughter. He’s pressed into service in the Bulgarian army, where he sees soldiers slaughter entire villages. Flogging is common and Candide himself is beaten nearly to death for desertion.

Cunégonde is presented at the beginning as a courtly romantic ideal. She is raped and disemboweled (though she survives) by invading soldiers and her family are butchered. Man is an animal. Although Cunégonde’s name is “real” in a medieval way, most interpreters agree that we’re supposed to think of female genitalia upon hearing it.

The various characters suffer slavery, mutilation, and betrayal: an old woman recounts being enslaved, her buttocks partially eaten by cannibals after her lover’s murder. This serves more than a rhetorical point; it’s supposed to be hilarious. The story takes them to Lisbon after the great earthquake14, an earthquake kills thousands, and Candide sees survivors hanged or burned in a religious purge. A sailor loots amid the quake’s ruins, indifferent to the dying.

Everyone is unrelentingly greedy and hypocritical. Candide makes it to a utopia, Eldorado, but decides to leave, because he craves Cunégonde for her wealth and her cuné. He is swindled by merchants and robbed by his own servant. He discovers that Cunégonde is now ugly and shrewish, while her pompous ass of a brother tries to kill Candide for honor’s sake.

Through it all, murder, rape, theft, and torture are casual constants.

Candide finally settles on a farm, "we must cultivate our garden", and everyone shrugs. Significantly, Candide settles in quietude within the territory of the Ottoman Empire, i.e. not within Christendom.

Candide is not capricious at all. It is not random, unpredictable, or whimsical. It is all of a pattern. Candide is set in a world without gods, the world of W. H. Auden’s The Shield of Achilles.

She looked over his shoulder

For athletes at their games,

Men and women in a dance

Moving their sweet limbs

Quick, quick, to music,

But there on the shining shield

His hands had set no dancing-floor

But a weed-choked field.

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy; a bird

Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third,

Were axioms to him, who'd never heard

Of any world where promises were kept,

Or one could weep because another wept.This is not a world where promises are kept.

Candide, of course, is no ordinary novel. It is exceptional. It is so utterly dreary that it hasn’t even Dávila’s single thorn of light.

Religion is fanaticism, democracy is reasonable

Both Candide and Quixote are highly episodic15 satires featuring highly naive/innocent characters. Although Voltaire is writing in a much more modern context, he makes sure to connect his satire to one of Cervantes’ biggest targets: Cunégonde is a mockery of the ideal of courtly love, which makes the lowly Candide a knight errant of sorts.

Voltaire would, of course, have read the Quixote, and surely the Spanish work influenced Candide16. Understand, however, that Voltaire would have hated Don Quixote himself. The melancholy knight would have represented the foolishness that led to all that was now wrong with the world, the fantasist edging to fanatic.

Here is Voltaire, from the compellingly composed (I intend no irony in saying this) entry for fanatisme in the Dictionnaire philosophique portatif:

Fanaticism is, in reference to superstition, what delirium is to fever, what rage is to anger. He who has ecstasies, visions, who takes dreams for realities, and his imaginations for prophecies, is an enthusiast; he who supports his madness with murder is a fanatic. Saint Bartholomew’s Day gave us a striking example of this; the massacre was the fruit of fanaticism heated by politics.

The most detestable example of fanaticism is that of the citizens of Paris who, on Saint Bartholomew’s night, rushed from house to house to stab, slaughter, and throw out of windows their fellow citizens who did not go to mass. There are cold-blooded fanatics, like those judges who condemn to death those who have done nothing but think differently from them; there are others who surrender themselves to transports, like those who, in the time of Cromwell, cut the throats of their neighbors while singing psalms.

The fanatic is almost always under the direction of a rogue who knows how to turn this delirium to his own profit. A fanatic’s mind is a volcano that throws out flames and ashes, and there are few examples of these volcanoes becoming extinguished without having caused damage.

The Spanish have given us a striking idea of fanaticism in their autos-da-fé. The Inquisition, which they borrowed from the popes, has made of this nation a people of executioners under the mask of religion. It is a curious thing that a nation so grave, whose genius has produced a Cervantes, a Lope de Vega, a Calderón, should have abandoned itself to such excesses. But it must be said that the Spaniards were not the inventors of this abomination; they received it from Rome, and they pushed it to the extreme.

What is the remedy for this contagious madness? Reason and time. Reason dissipates fanaticism as the sun dissipates fog; but it takes time for reason to spread among men, and meanwhile the fanatics make victims.

Voltaire’s conclusion is the positive statement of the modernist agenda, of the great democratic project. The problem is the fantasy of God, the divine delusion.

But even for Voltaire the remedy is not precisely what he says it is. Immediately after “fanatics make victims”, he says this:

We have seen fanatics in all sects, among Jews, Christians, Muslims; there are even fanatics among the Confucians, though they are rarer. The only way to prevent this evil is to have no dominant religion, to let each man think as he pleases, and to punish only actions, not thoughts.

The real remedy is above-us-only-sky.

You will recognize in this the dominant Enlightenment story, that religion is the root of evil, that the Wars of Religion mean that religion is war.

Religion is fanaticism. Reason will resolve all this.

How is the Quixote undemocratic?

In practice Voltaire and Rousseau consign us to the world of Kafka, Heller, and Orwell.

The Enlightenment has saved us from the hot-blooded fanatics only to give us over to the cold-blooded fanatics, “like those judges who condemn to death those who have done nothing but think differently from them”.

As our world sits under a godless sky and between the second and third forms of democracy, most of us have no lens through which to view the Quixote but the one which hates all dream and divinity, which craves a dusty world of deathlessness rather than life.

At last we can answer the question. How is the Quixote undemocratic?

The Quixote is not absurd

Democracy is absurd, and I mean this most philosophically. Absurdity has become something to be embraced, serious as a heart attack, by any pretenders to being denominated thinking men. Camus and Sartre, Waiting for Godot and The Dumb Waiter. The democratic project cannot be achieved if there is any transcendent meaning at all. Reason is incapable of finding meaning, as Descartes’ death-spiral daemon showed us. Since meaning is impossible, absurdity becomes a value, becomes the human value. In this great philosophical sense, it has been decided by Enlightenment-modern thinkers, by democratic thinkers, that the Quixote is absurd.

They are wrong, and I urge you to recast your vision. Quixote is not absurd. It is ridiculous. This is a fundamental distinction the democrat in his humorlessness cannot make. The absurd purposefully abjures meaning; the ridiculous must refer to some meaning in order to exist.

Mistaking a pair of whores for noblewomen and addressing them chivalrously is ridiculous rather than absurd. It tethers itself to an ideal, and by its ridiculousness tugs at the tether: can chivalry hold this weight?

The Quixote is full of love

The Quixote is warm and affectionate; not for nothing do the Spanish love the noble knight. Nobody loves Candide.

Democratic man is incapable of love. Perhaps more horribly, he is void of affections. The democratic replacement for affections is appetites. The replacement for love is lust. Pangloss loses eye and limb to syphilis; Candide wants the cuné. Quixote is chaste, but not easily; he strives for an ideal. Dulcinea he keeps at dreamy remove, he is immune to the shepherds’ lust for Marcela, he insists to Maritornes that honor binds him to be faithful to Dulcinea.

He has never met Dulcinea, and will not allow himself to consider that she is a rough-handed farm girl who smells of garlic. It is absolutely ridiculous. It is even problematic. But it is not democratic; rather, it is the worst and best of nobility. It is testing the tether to heaven.

A godless sky cannot suffer fantasy; the only thing that redeems fantasy is metaphor, is the meaning beyond. The democrat may use the word ridiculous (as I often use the word absurd) in a non-ultimate sense, but ultimately, in these quixotic episodes he can see only absurdity. What can they mean but that there is no meaning?

The Quixote gives transcendent meaning to suffering

In both Quixote and Candide real suffering surrounds the protagonists, and in fact they cause real suffering, especially Don Quixote. In Candide this is laid absurdly at the feet of the God who must not exist. Why all this suffering in Quixote? The democrat understands it absurdly.

The suffering Don Quixote causes has meaning, a message for us. The satire in Cervantes’ book challenges us to create a better world.

The courtly love that overtook chivalry, as expressed in the novels and poems that Cervantes has burned in chapter six of his own book, was pagan rather than Christian. Love and honor were not actually at the service of God and man; rather, they enslaved the knight and justified his adulteries. Marriage and the divine order mean nothing in the face of the lust of compelling “love”. Etienne Gilson and C. S. Lewis have done excellent work in pursuit of this.17

The harm that Don Quixote does is in service of this pagan ideal. Cervantes has not penned a polemic contra love, but a satire urging us to see the virtue of balanced, harmonious love. How happy would Don Quixote have been if he could have kept his sanity and brought his modest marriage suit to a plain hard-working country girl?

Democracy ends in absurdity. So tethered to heaven is the Quixote that the knight of sad semblance must, at his death-bed and the end of the book, regain his reason and ready for heaven.

I was mad, and now I am sane; I was Don Quixote of La Mancha, and now I am, as I have said, Alonso Quixano the Good. May my repentance and my truth restore me to the esteem you once had for me.

Those cursed books of chivalry, which I read and which brought me to this pass, have been my ruin; but now, by God’s mercy, I abhor them.

My dear friends, I feel that I am rapidly approaching my end. No more jesting now; let me have a confessor to shrive me, and a notary to draw up my will. In such straits as these a man cannot trifle with his soul; and while the priest is shriving me, let someone fetch the notary.

Shed a tear, for the love of God.

Here there is no repudiation of love, of goodness, of mercy. Reason is embraced, as is faith, as is repentance, as is loyalty and faithfulness to friends. And yet, democratic man insists on the absurdity of quixotism.

The Quixote affirms the worth of human life

Don Quixote ends, significantly, among friends. The knight of sad semblance is given a death loaded with meaning, because this is a story that believes life has meaning. None of the satire is purposeless or absurd, and our knight has striven for nobility, albeit errant in his path. This is a story like those described by Dávila at the top of this piece, not photorealistic or “gritty”, but symbolic: tragedy, lyrical poetry, and the tale itself submit the representation of life to their own whimsical purposes. They disdain faithful reproduction, and nothing ties them to the monotony of our common condition. Upon the scaffolding that they quickly throw up an astute system of gestures elaborates a noble effigy of Man.

It has something good to say, including that life is worth the adventure.

The Quixote is thoroughly Christian

The democrat has no religion but anthropotheism. Just as Enlightened man and Candide reject God, they understand Quixote to be working toward the same, within their myth of progress of which they are the current culmen (whatever is now is always the culmen).

But Cervantes is not satirizing Christianity or religious faith. He is ridiculing the Spanish church; if you wish to say he is ridiculing the capital-C Church I have no real objection. The Quixote must be understood in a Reformational context. Laying aside any scholarship done exploring the idea that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo18 or crypto-Protestant, or his residence and relatives in the city of books and Bibles and Inquisition and Reformation that Sevilla19 was, he lived during a time of widespread abuse by the Spanish church, and was not alone in objecting to it, both within Spain and without. He simply made his objections in such a way that their most Catholic majesties and their offices of Inquisition would grant a printing license.

So modern are most readers that they cannot see that the episodes involving the Holy Brotherhood involve not a religious order but a national police force, formed centuries before, whose charter came from the king. The “Holy” was added to align the force with the crusading nature of the late Reconquista. The same is true of the Inquisition, which responded not to Rome or to the Catholic Church, but to the crown. This is not to say that they did not have religious characters; rather, it is to place the Inquisition and much of Cervantes’ religious satire in the context of the first stage of the great democratic project. “The state that esteems itself sole judge of its own actions and the final court of appeal to its own plaints, that complies only with that which its own will adopts, whose own interests are the supreme law, and therefore makes itself a secularized god.”

At no point does Cervantes, veteran of Lepanto and thoroughgoing Spaniard, challenge God. The democratic man has no conception that there may exist a distinction between Christian faith and Christian institutions.

Finis

The Quixote is said to be the first modern novel because it is supposed to be part of the only true story of modernity: we are shedding religion in favor of democracy and anthropotheism. There is an agenda to this interpretation, an interpretation that is widely accepted even by readers who love and admire the transcendent, for we are all infected with the debasement of democracy.

It takes a disingenuous reading of the ingenuous knight to imagine this book to be anything but a work of exaltive glory.

No more jesting now; let me have a confessor to shrive me, and a notary to draw up my will. In such straits as these a man cannot trifle with his soul.

Postlude

Now that you have reached the end, having had faith in me, I will tell you that I am in no way against republics or citizen votes. I am simply against man as god and the mob-god. This has been a philosophical-theological piece rather than a political one.

Good night.

All translations of Dávila in this piece are my own.

Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Textos (Girona: Ediciones Atalanta, 2010), 85-86.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 62-63.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 76.

This explains some of Dante’s fascination with and love for the Roman Empire. A strong empire could hold in check the runaway power of his day, which had adversely affected his country, his cause, and his person.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 76.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 77.

“The sovereignty of the state contests the divine right of kings, which is not a religious formulation of political absolutism, but rather the most effective doctrinal way to deny it. To proclaim the divine right of the monarch is to give the lie to his sovereignty and repudiate the irrecusable validity of his actions. Upon the monarch of divine right lies the imperious juridical weight of the religion that anoints him, the natural law that precedes it, and the morality that cows it into obedience.” Gómez Dávila, Textos, 78.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 79.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 81.

Gómez Dávila, Textos, 82.

Lewis White Beck, Early German Philosophy: Kant and His Predecessors (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969), 201.

An ancient, and not particularly Christian, idea. Whatever the greatest good is, that is what we call God. God is what we call the greatest good. For someone like Leibniz, this meant a personal God; for someone like Aristotle, not so much.

This famous disaster is said to part of Voltaire’s inspiration to write Candide. How could a good God...?

A feature of medieval novels which irritates modern readers. Candide is so short there are seldom complaints, but the Quixote is one thousand pages of episodes I think delightful. Get into the format, have some fun!

Not alone, of course. This was an age for satirical novels/novelettes. Think Jonathan Swift.

See Lewis’ Allegory of Love, Gilson’s The Mystical Theology of Saint Bernard, and Denis de Rougemont’s Love in the Western World.

A converted Jew or even their descendants, existing in the context of the forced conversion or expulsion of Jews in 1491.

Sevilla was the center of the Reformation in Spain, headed up by the monks of the Order of Saint Jerome, from whom came Casiodoro Reina, the modern Bible in Spanish, and the first Protestant creed written in Spanish.

This article has been a comfort to me in illness. Thank you.

This is the type of article I expected to study at uni. Obviously, that is not what happened. Glad to be able to read it now, it's brilliant.